Description

When discussing religion in the globalized world, scholars usually operate under several standard assumptions. First, they proceed from the modern supposition that religion should be separated from the state and, therefore, should not engage in public discourse but rather limit its sphere of influence to personal spirituality and salvation. Second, they usually discuss well-established religious traditions that have been evolving for centuries while paying less attention to new religious movements since their membership is relatively low and so, as they think, is their impact on the global stage. Third, those scholars focus their analysis on the “religious disruptors,” i. e., those sects and groups that defy social norms and represent a threat to civilization. As a result, examining Islamic terrorism or various apocalyptic cults often stands at the center of religious studies in the global context.

It is easy to show that all those assumptions largely oversimplify the role religion and religious beliefs play in society, whether on a local, national, or global level. Catholic views on the death penalty and abortion, for instance, are an inalienable part of public discourse on governmental policy in the United States. Modern religious movements, like Mormonism, with its almost two hundred years of existence and now more than sixteen million adherents worldwide, have a growing impact in society’s life. An American politician, businessman, and an LDS minister, Mitt Romney was the Republican Party’s nominee for President of the United States in the 2012 election. Finally, in our global world, torn apart by cultural divisions and prejudice, religious scholars should undoubtedly pay closer attention to the unifying and value-oriented aspects of spiritual teachings rather than their harmful and militant elements.

There is one more factor that implicitly influences the discussion of religious issues in the contemporary era. It is the collapse of the USSR that took place several decades ago and was entirely unexpected for both the communist bloc countries and their liberal democratic opponents. The whole past century passed under the banner of God’s “death,” which resulted in the collapse of organized religion and the flourishing of secular culture. Religious scholars of the twenty-first century talk instead about the resurrection of faith and “post-secular age.” However, no one seems to propose a plausible explanation for the seventy-five years of the existence of the Soviet Union — the only irreligious empire in the entire human history. Theodore Adorno famously remarked about the Nazi Holocaust’s horrors that “to write a poem after Auschwitz is barbaric.” Then what about pursuing theological studies after the Gulag? After all, the Soviet atrocities vastly surpassed the crimes of the Nazi regime. Yet, the existential mystery of the atheist outburst in Russia did not receive, in my opinion, adequate and exhaustive explanation both in its native land and the rest of the intellectual world.

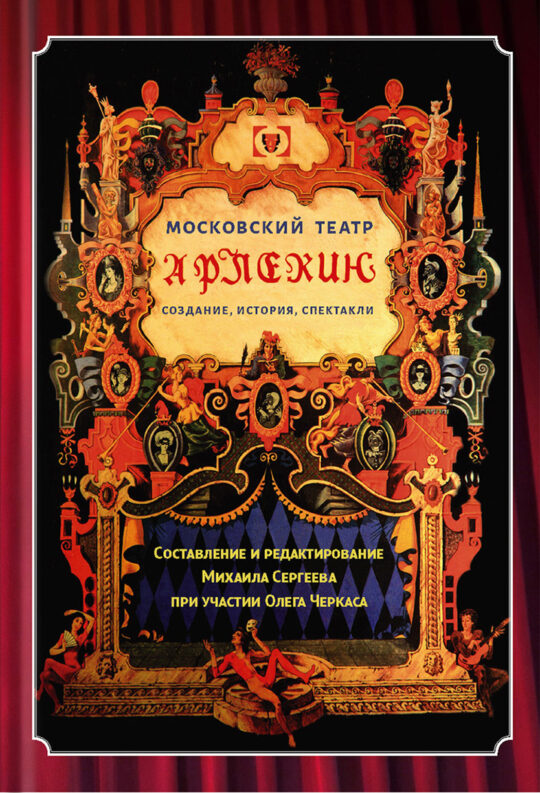

Mikhail Sergeev (b. 1960) — Ph.D. in philosophy of religion (1997, Temple University, Philadelphia, USA); adjunct professor of the history of religions, philosophy, and contemporary art at the University of the Arts in Philadelphia. Sergeev served as (co-)chair of the department of religion, philosophy, and theology at Wilmette Institute (2017–21). The author of more than two hundred scholarly, journalistic, and creative works, he published them in the United States, Canada, Japan, Poland, Greece, the Czech Republic, the Netherlands, Uzbekistan, and Russia. Sergeev has authored and edited twelve books, including the monograph, Theory of Religious Cycles: Tradition, Modernity, and the Bahá’í Faith, (Brill, 2015) and his latest, Russian Philosophy in the Twenty-First Century: An Anthology (Brill, 2020).

Mikhail Sergeev (b. 1960) — Ph.D. in philosophy of religion (1997, Temple University, Philadelphia, USA); adjunct professor of the history of religions, philosophy, and contemporary art at the University of the Arts in Philadelphia. Sergeev served as (co-)chair of the department of religion, philosophy, and theology at Wilmette Institute (2017–21). The author of more than two hundred scholarly, journalistic, and creative works, he published them in the United States, Canada, Japan, Poland, Greece, the Czech Republic, the Netherlands, Uzbekistan, and Russia. Sergeev has authored and edited twelve books, including the monograph, Theory of Religious Cycles: Tradition, Modernity, and the Bahá’í Faith, (Brill, 2015) and his latest, Russian Philosophy in the Twenty-First Century: An Anthology (Brill, 2020).

Reviews

There are no reviews yet.