Description

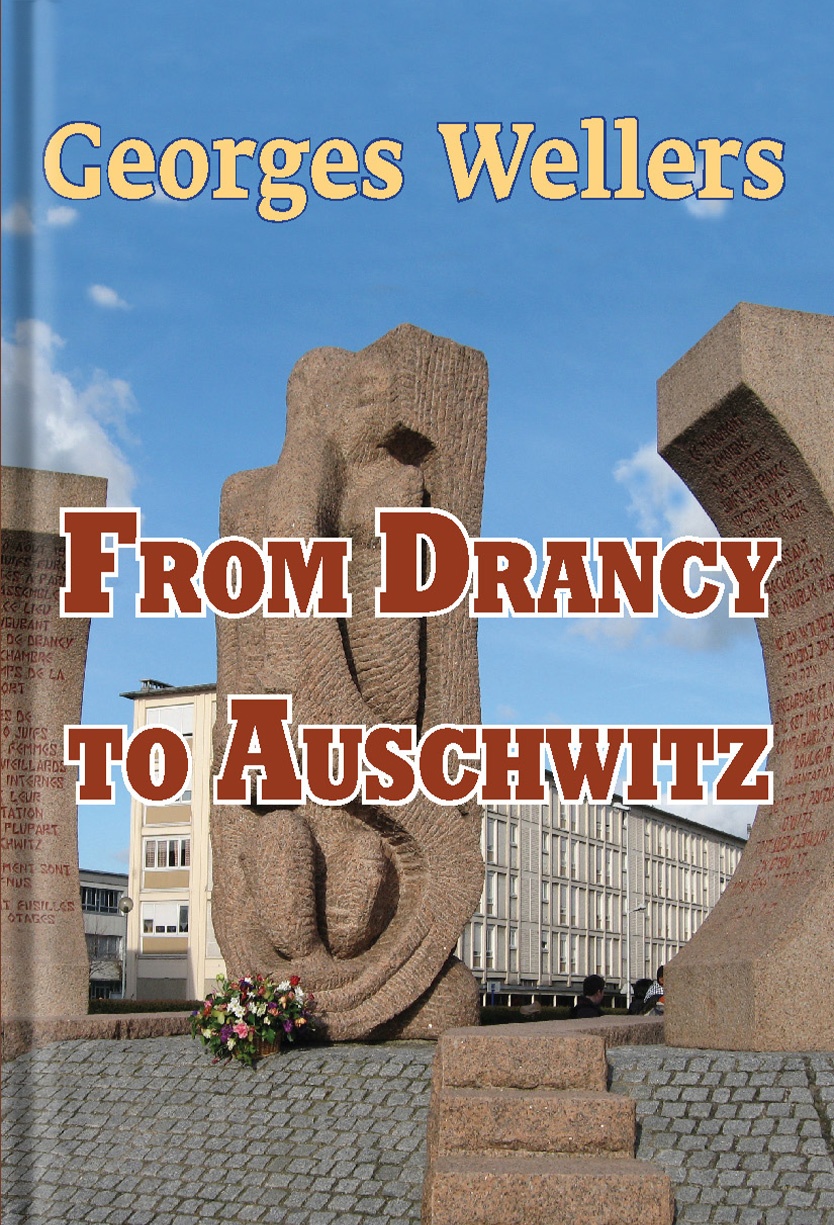

Part One is a meticulous description, with a scientist’s precision, of the Drancy camp throughout its existence.

Part Two is a personal and emotional description of several people whom George befriended in the camps, from prominent individuals much older than he was at that time to teenagers whom he helped to survive at amazing risk to himself and self-sacrifice that might be expected towards one’s own sons. It takes the reader to Auschwitz and the death march to Buchenwald after its liquidation. Although the book is entitled “From Drancy to Auschwitz” it was Buchenwald where George was liberated by the Americans.

From the translator

George did not talk much about his captivity, even many years later when we first met in Moscow in 1960. His wife Anna mentioned that when he returned home from Buchenwald he spent weeks in bed, facing the wall. And yet, this book was published in 1946. It means that he wrote it very soon after regaining his physical and emotional strength. Even if he managed to keep notes in the camps, in his microscopic handwriting that amazed me in his letters, he must have made good use of the obsessive German record-keeping to produce all the dates and numbers of deportees that the reader found in this book.

He published several other books about the Holocaust, but this one was never translated. Until now. A group of enthusiasts decided to dedicate its Russian and English translations to the memory of those who perished, and those who survived against all odds, so that the younger generation can learn about the Nazi persecution of the Jews from a firsthand account at a time when anti-Semitism is raising its ugly head in so many countries that should know better.

George’s older siblings in Moscow did not know that he survived the war. My father died almost two years before his first letter arrived during the Khrushchev “thaw”— during the war no correspondence with foreign countries was allowed at all, and for many years after the war was very restricted and perlustrated by the KGB, and George realized that a letter from him would damage his siblings’ reputation.

Despite all the deprivations during his captivity, George lived a long a productive life. He died in Paris in 1991 at the age of 86. He excelled in a prominent scientific career, was awarded the Legion of Honor rosette as its Officer, was Vice-President of the Association of Nazi-camp survivors of France.

He was the only French witness at the Eichmann trial in Israel. Transcripts of his three hours of testimony about the deportation of children are available on the Internet and you can see also video of his testimony (in French with English translation from about 6th min to 35th min).

Olga Weller-Lifson

Georges Wellers was born in Russia in 1905 (The “s” was added to the name to allow the French to pronounce it correctly, not like Wellé).

Georges Wellers was born in Russia in 1905 (The “s” was added to the name to allow the French to pronounce it correctly, not like Wellé).

Reviews

There are no reviews yet.